|

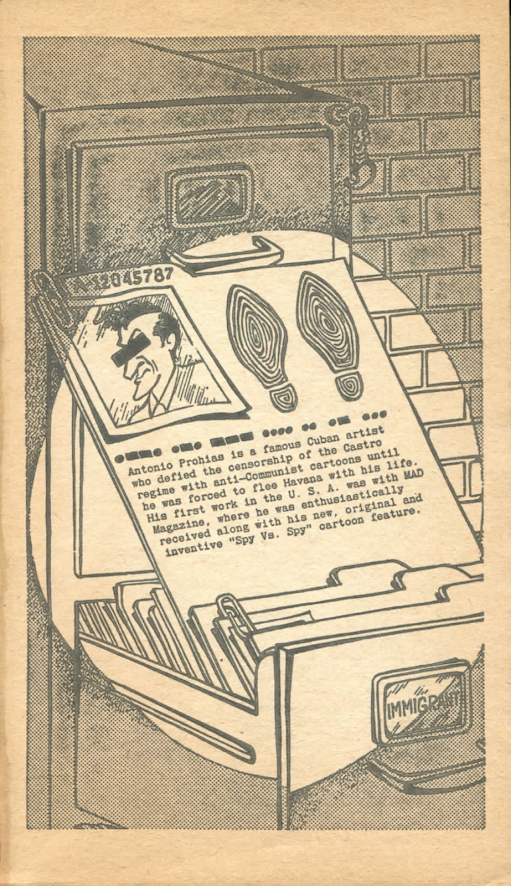

| The cover of The All New Mad Secret File on Spy vs Spy by Antonio Prohías, his first such collection, published by Signet in 1965, plus the inside biography of the cartoonist. |

Saturday, May 1, 2021

Antonio Prohías (1921-1998)

Thursday, April 1, 2021

Ernest Kurt Barth (1929-2001)

Last time I wrote about Lou and Zena Shumsky, authors of the young person's novel First Flight (1962). (She was really the author. Her husband was more of a technical advisor.) This time I would like to write about the illustrator of their book, Ernest Kurt Barth.

Ernest Kurt "Ernie" Barth was born on March 23, 1929, in Rockville Centre, New York, to Ernest and Paula K. (Meeh) Barth. His parents were born in Germany and arrived in America only shortly before his birth. The elder Ernest Barth was a painting contractor but also, as his son remembered, a hobbyist. Ernie Barth was thus well prepared for illustrating a book about boys who build and fly model airplanes.

Ernest K. Barth graduated from Memorial High School in West New York, New Jersey, and served for two years in the U.S. Marine Corps. He applied his G.I. Bill benefits to his education in art at the Pratt Institute in Brooklyn. He graduated with a bachelor's degree in fine arts in 1952. I suspect that he also met his future wife at Pratt.

Ernest Barth had a varied career in art. He worked for a firm called Cellomatic in the early days of television animation. In 1954, he served as an assistant to Al Capp (1909-1979) on the syndicated comic strip Li'l Abner. (Frank Frazetta [1928-2010] was another of Capp's assistants at the time.) From 1953 to 1957, Barth created cover art and interior illustrations for science fiction magazines. Afterwards, he expanded into illustrating books for Dell, Harper & Row, and Random House. Later in life, while living and working in Tuxedo Park, New York, he worked as a graphic artist and commercial artist.

Barth's first wife, Eileen Ann Furlong Barth (1931-1986), was also an artist and a teacher of art at Monroe-Woodbury High School in Woodbury, New York. She was the daughter of Raymond H. Furlong, a printer for the New York Times, and Anna (Ungerer) Furlong, a bank clerk. The Barths and their two daughters lived in San Miguel De Allende, Mexico, for a year in 1973-1974, where Eileen Barth received her master's degree in fine arts. Eileen Ann Furlong Barth died tragically young of cancer. Her husband remarried. He died on March 28, 2001, in Tuxedo Park. His remains were cremated and the ashes scattered, fittingly, by airplane over Orange County, New York.

One of the reasons that I have wanted to write about Ernest Kurt Barth is to show his artwork in the fields of science fiction and fantasy. The Internet Speculative Fiction Database (ISFDb) has a list--actually two lists--of his credits in those fields. I would like to acknowledge that website and to expand on the available biographical information on him. (Find A Grave has a fuller biography than what I have written here, and so I would also like to acknowledge Von Rothenberger, who posted it, along with a photo of Barth, to that site.) There are two entries on the ISFDb on Barth, one for Ernie Barth, the other for Ernest K. Barth. My hope is that those two entries will be combined and that Barth will receive his full due as an artist.

Ernie Barth's cover for Fantastic, October 1954. He was twenty-five when this picture was published. The cover story was "The Yellow Needle" by Gerald Vance.

|

| Finally, Barth's illustration for "Forced Move," a short story by Henry Lee, published in Worlds of If, June 1955. |

Text copyright 2021 Terence E. Hanley

Wednesday, February 17, 2021

Lou & Zena Shumsky

- The Year of the Dream (young adult fiction, 1962), illustrated by Harper Johnson

- A Tangled Web (young adult fiction, 1967)

- Seven for the People (young adult nonfiction, 1979)

- Next Time I'll Know (young adult fiction, 1981)

- A Cooler Climate (adult novel, 1990)

- Ghost Note (adult novel, 1992)

- "Family Affair," Canadian Home Journal (Nov. 1957)

- "The Innocents," McCall's (Aug. 1964)

- "Trial by Night," Alfred Hitchcock's Mystery Magazine (Jan. 1974)

- "Accomplices," Alaska Quarterly Review (Fall/Winter 1985)

Wednesday, January 20, 2021

Iris Owens (1929-2008)

Iris Klein attended Barnard College and is supposed to have graduated from Brooklyn College. She was married twice before age thirty and divorced in pretty short order. She never again married and died without having any children of her own.

Iris moved to Paris in the 1950s and wrote or co-wrote five pornographic novels for Olympia Press under the name Harriet Daimler, what reviewer and novelist Herbert Gold called her nom de cochon ("pig name"). She returned to the United States in 1970 and took up residence again in New York City. Just two more books flowed from her pen, After Claude, from 1973, and Hope Diamond Refuses, from 1984. In 1975 she taught a creative writing workshop at Great Meadow Correctional Facility in Comstock, New York. As the years went by, Iris Owens made fewer and fewer forays from her apartment. Late in life (or maybe not so late) she was, according to accounts, a shut-in. Even the New York Times failed to take note of her death, which came on May 20, 2008. Described during her life and afterwards as ageless, timelessly beautiful, even Junoesque in her stature and appearance, she was seventy-eight years old when the end came.

The narrator of After Claude is a young woman writer who has returned to New York after having lived in Paris. Her name--or maybe we can call it a meta-name--is Harriet Daimler. Herbert Gold (who is still with us) reviewed After Claude for the San Francisco Examiner (July 1, 1973, p. 188), writing: "Owens Qua Daimler [has] proved one of the most important triple-headed theses of modern times: That at one and the same time a woman writer can be (1) funny, (2) pornographic and (3) ladylike." The book is indeed funny--hilarious might be a better word for it--until it isn't anymore. Like Portnoy's Complaint by Philip Roth (1969), it is a funny book about serious things and ends in a kind of sadness and loss. Mr. Gold wrote: "This book dissolves finally in hysteria, the satire troubled by real pain, and the curious abandon at the end of the book adds a dimension of pathos which is against the principles of your standard black humorist."

I snapped this book up when I saw it because of the blurbs on the cover, because it is a fairly short novel (only 219 pages), but mostly because of the cover with its classic 1970s photo illustration and typography, more so because of the classic 1970s look of the cover model. The photographer is Neal Slavin, who is also still with us. I wonder if we'll ever know the name of his subject (although she looks a little or a lot like the actress Jenny O'Hara).

If you would like to read more about Iris Owens, try "Iris Owens: Wit of the Bitch," by Izabella Scott, by clicking here. A list of books by Iris Owens, from the website Wikipedia:

As Harriet Daimler:

- Darling (1956)

- The Pleasure Thieves, with Marilyn Meeske, who wrote under the pseudonym Henry Crannach (1956)*

- Innocence (1957)

- The Organization (1957)

- Woman (reissued as The Woman Thing) (1958)

As Iris Owens:

- After Claude (1973)

- Hope Diamond Refuses (1984)